Highlights

- From 2001, remittances put the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) in a central role in reshaping the Philippine economy.

- The BSP’s able management of monetary policy and banking supervision oversaw a period of exceptional growth and stability.

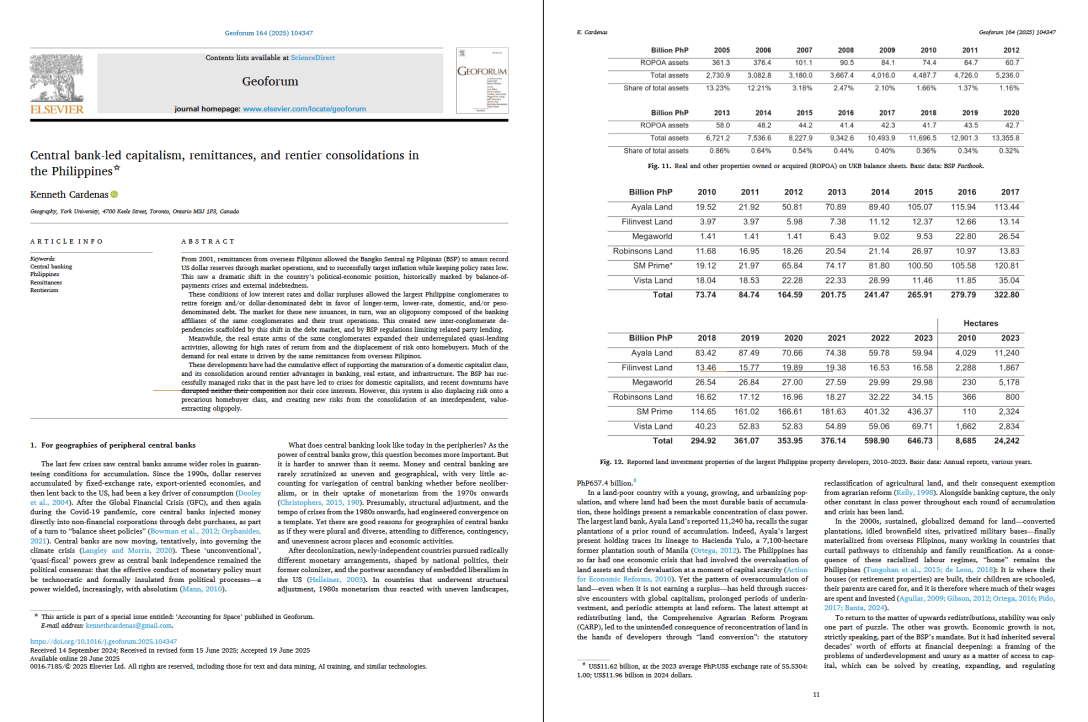

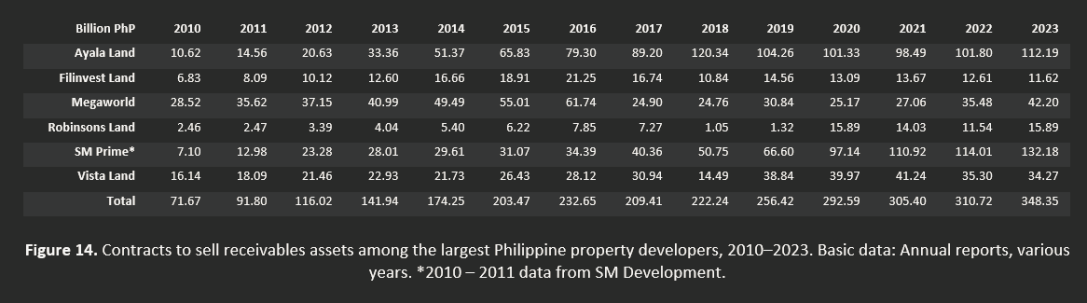

- Philippine conglomerates with interests in real estate, infrastructure, and banking consolidated their position.

- New concentrations of risk have arisen from changes in the debt patterns among these conglomerates.

- Shadow banking practices by their real estate subsidiaries have also displaced risk onto homebuyers.

Abstract

From 2001, remittances from overseas Filipinos allowed the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) to amass record US dollar reserves through market operations, and to successfully target inflation while keeping policy rates low. This saw a dramatic shift in the country’s political-economic position, historically marked by balance-of-payments crises and external indebtedness.

These conditions of low interest rates and dollar surpluses allowed the largest Philippine conglomerates to retire foreign and/or dollar-denominated debt in favor of longer-term, lower-rate, domestic, and/or peso-denominated debt. The market for these new issuances, in turn, was an oligopsony composed of the banking affiliates of the same conglomerates and their trust operations. This created new inter-conglomerate dependencies scaffolded by this shift in the debt market, and by BSP regulations limiting related party lending.

Meanwhile, the real estate arms of the same conglomerates expanded their underregulated quasi-lending activities, allowing for high rates of return from and the displacement of risk onto homebuyers. Much of the demand for real estate is driven by the same remittances from overseas Filipinos.

These developments have had the cumulative effect of supporting the maturation of a domestic capitalist class, and its consolidation around rentier advantages in banking, real estate, and infrastructure. The BSP has successfully managed risks that in the past have led to crises for domestic capitalists, and recent downturns have disrupted neither their composition nor their core interests. However, this system is also displacing risk onto a precarious homebuyer class, and creating new risks from the consolidation of an interdependent, value-extracting oligopoly.

This article appears in a special issue of Geoforum on the theme Accounting for Space.

It is the final form of work I had previously presented at the 2025 Annual AAG Meeting in Detroit, and at the Accounting for Space: A critical accounting / critical geography mini-conference in 2023.