For political imagination, and for varieties of possibility

Open file no. 50, began 24 October 2023

Sa sandaling matutunan mo ang managinip nang lubusang gising,

na ibalanse ang kamalayan hindi sa talim ng pangangatwiran

ngunit sa dobleng katig ng katwiran at panaginip;

sa sandaling matutunan mo ito,

mabibitawan mo lamang ito sa oras na mabitawan mo

kung paano magisip.

Ursula K. Le Guin, Ang Salita Para Sa Daigdig Ay Gubat

Ang tunay na radikal ay ang gawing abot-kamay ang pag-asa,

hindi ang patunayan ang pagka-gipit.

Raymond Williams

As I wrap up my dissertation, and as I take part in conversations about energy transitions, alternative transnational economies and solidarities, and climate crisis responses other than war, I have found myself turning and returning to two premises.

These arose as I came to my own understanding of how accumulation and class power had developed in the Philippines over five centuries of capitalist and colonial encounter.

I am finding, again and again, that many analytical categories that had developed in response to realities found elsewhere have very limited usefulness here.

This incongruency between concepts and realities is hinted at by the recurrent (evergreen?) mode of production debates within Philippine critical thought: is the Philippines a capitalist society, or is it semi-feudal, semi-colonial?

Maybe it is both and neither: the debate continues because both descriptions help explain some features of the systems we wish to describe and resist. Yet neither does justice to life as it arises within, alongside, and outside these systems.

If you and I agree, then we need to trace the reasons behind the poor conceptual fit.

These two premises also arose out of wanting to make hope possible, not despair convincing. I want to react to the rigid radicalism and damage-based research that I keep running into—and keep reproducing, myself.

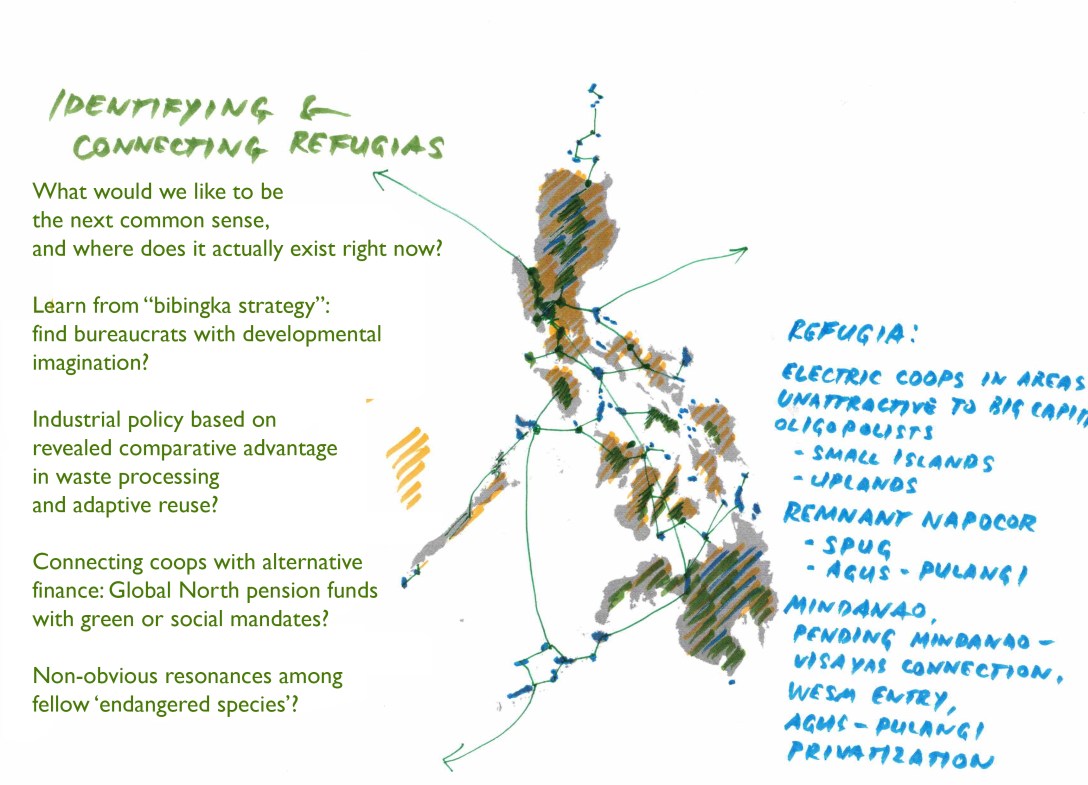

If the whole point of ‘theory’ is ‘seeing’, I would much rather now learn ways of seeing that open up rather than foreclose political imagination. Instead of learning how to see lack, I would rather learn how to see varieties of possibility—especially in landscapes dismissed as wastelands.

If you and I agree, then we need to find a way to take part in conversations in a way that brings these abilities out—even among the most inflexible critical theory bores in our worlds.

Some rough, ongoing thoughts, under constant revision, shared here so we can pick up where we left off:

Continue reading “Two premises”